A History of England from the Landing of Julius Caesar to the Present Day

by H. O. Arnold-Forster

Part 2:

Related Page:

Chapter 59. Anne -- The Last of the Stuarts. 1702-1714.

59 The Queen (Anne) and her Councillors.

59 The War with France

59 Triumph of Marlborough.

59 The Tories in Office

59 Fall of Marlborough

59 The Last of the Stuarts

59 Union with Scotland

Chapter 60. Constitutional History of the Stuart Period.

60 (Stuarts) Magna Charta Re-enacted

60 Responsibility of Ministers -- The "Cabinet."

60 The House of Commons and the People of England

Chapter 61. Literature in the Stuart Period

61 Milton, the Puritan Poet

61 Puritan Prose-Writers.

61 Other Poets and Prose-Writers of the Early Stuart Period

Chapter 62. Writers of the Later Stuart Period.

62 The Essayists

62 Pope -- Early Newspapers

Chapter 63. Science, Art, and Daily Life Under the Stuarts.

63 The Royal Society -- Newton and Wren -- Harvey

63 Population Prices Wages Art.

Chapter 64. George I. 1714-1727.

64 The German King

64 Why King George Found a Welcome

64 The Beginning of Troubles

64 "The 'Fifteen" -- Success

64 "The 'Fifteen" -- Failure

64 England and the Quarrels of Europe

64 About the Country's Debts

The South Sea Bubble

Chapter 65. George II. 1727-1760.

65 George II. and His Great Prime Minister. -- Peace

65 "Jenkins's Ear," and War at Last

65 Continental Quarrels, and the Rise of Prussia

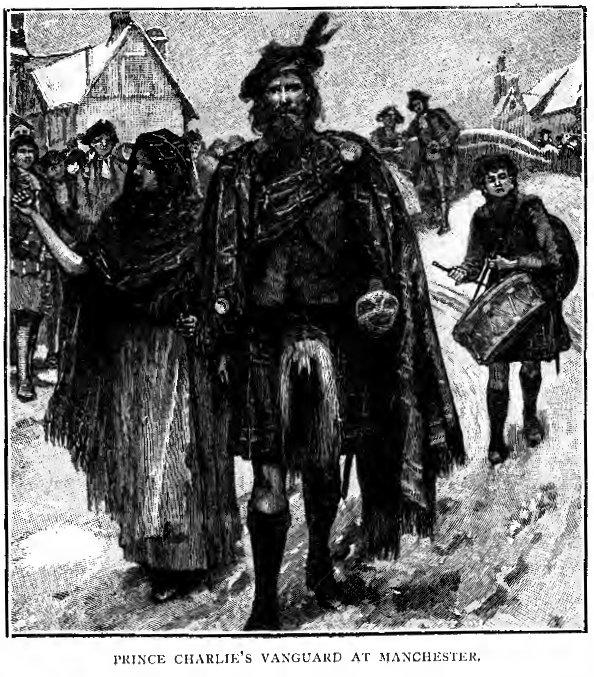

65 The "Young Pretender" and His Friends

65 The "Forty-Five."

65 The March to Derby -- Culloden

65 The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle

65 War by Land and Sea -- The Loss of Minorca

Chapter 66. Clive, Wolfe, and Washington.

66 War -- England and France in India and America

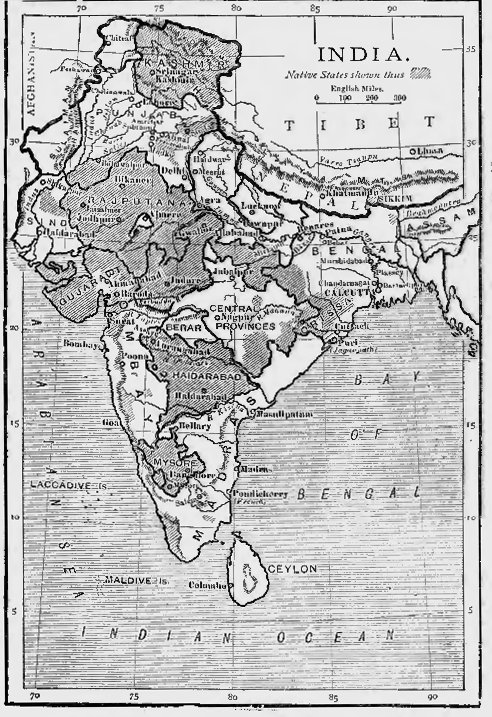

66 Clive

66 Battle of Plassey, and the Conquest of Bengal

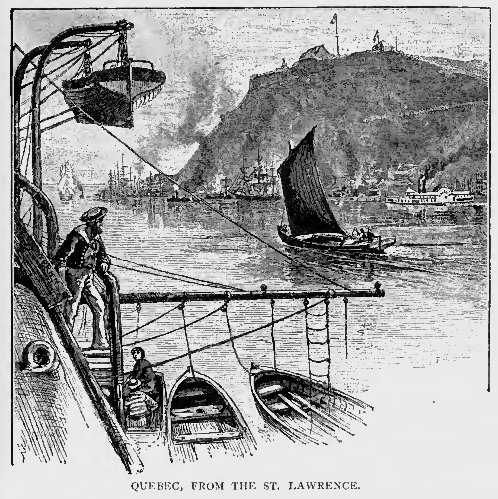

66 Wolfe

66 A Wonderful Year. 1759 -- John Wesley

Chapter 67. George III. 1760-1820.

67 "George, George, be King."

67 American Colonies and the Stamp Act

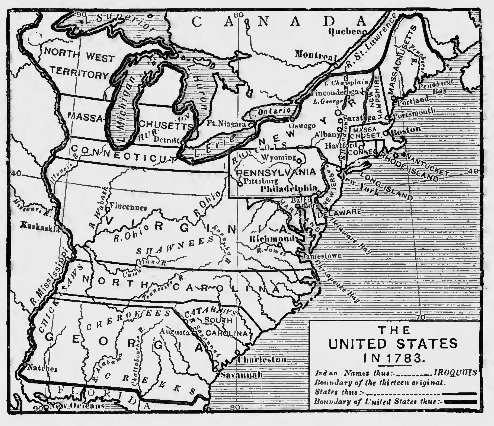

67 Washington, and the Declaration of Independence

67 Surrender of Yorktown, and the End of the War

67 "The Darkest Hour Comes Before the Dawn." -- "United Empire Loyalists."

Chapter 68. The Act of Union With Ireland.

68 Pitt and Fox

68 Great Britain and Ireland

68 Grattan's Parliament and the Act of Union

Chapter 69. The French Revolution.

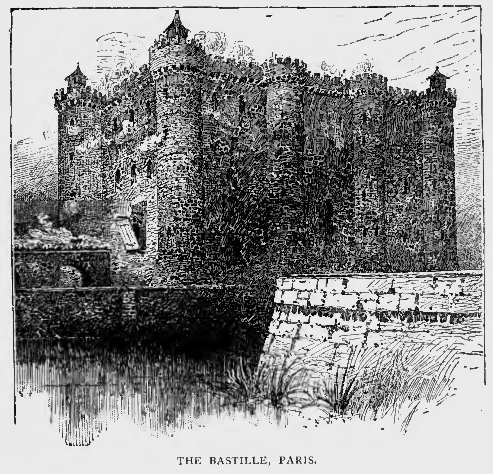

69 The Beginning of the [French] Revolution

69 Death of Louis XVI.

69 Great Britain and the Revolution. -- The British Navy

Chapter 70. The Great War with France.

70 Part I. Napoleon Buonaparte

70 Mutiny of the Fleet

70 "The Nile," and the Defence of Acre

70 "Armed Neutrality." -- The Battle of Copenhagen and Peace of Amiens

70 War Again

70 Boulogne -- Trafalgar

70 Austerlitz. Fox in Office

Chapter 71. The Great War with France.

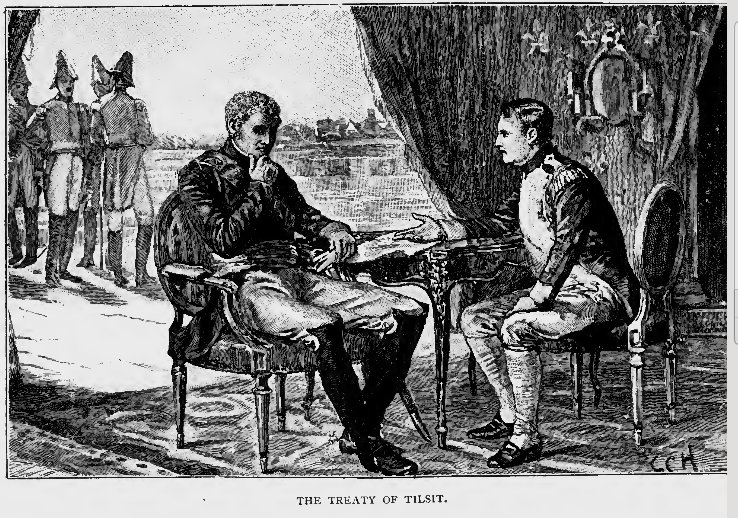

71 Part II. Buonaparte Master of Europe -- Jena -- Eylau.

71 Wellesley in India -- "The Continental System."

71 War on Land -- The Peninsula -- Failure

71 Walcheren Expedition -- Victories in the Peninsula

71 The Russian Campaign -- The Abdication of the Emperor -- War with the United States

71 The "Hundred Days," and Waterloo.

71 The Prisoner of St. Helena

Chapter 72. George IV. and William IV. -- The Great Peace 1820-1837.

72 The Regency -- George IV. -- Navarino.

72 Catholic Emancipation and Reform -- Slavery -- The Factory Act.

Chapter 73 The Days of Queen Victoria. 1837-1852.

73. Canada -- The Chartists.

73 The Anti-Corn-Law League -- The Potato Famine.

73 Troubles in the Year "Forty-Eight."

Chapter 74. The End of the Great Peace and the Story of Our Own Times. 1852-1901.

74 The Death of the Great Duke.

74 The Crimean War

74 The Conquest of Scinde and the Indian Mutiny

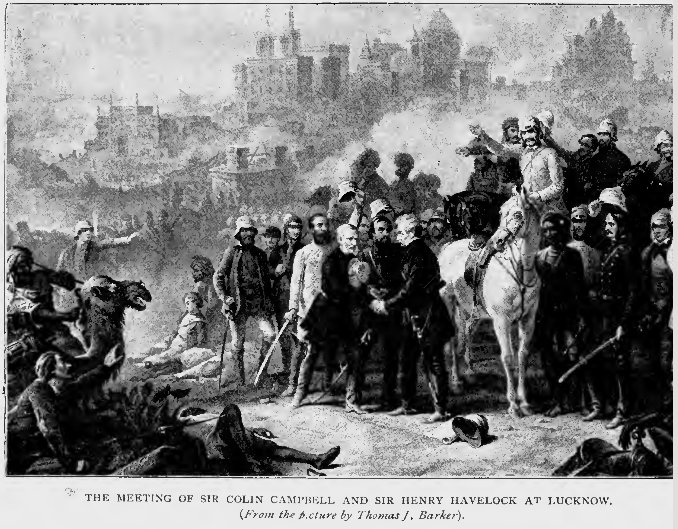

74 Cawnpore -- Lucknow -- Delhi

74 The Volunteer Movement.

74 The Civil War in the United States -- The "Alabama" -- The Geneva Award

74 The Cotton Famine

74 Our Own Times

Chapter 75. The Conquests of Peace.

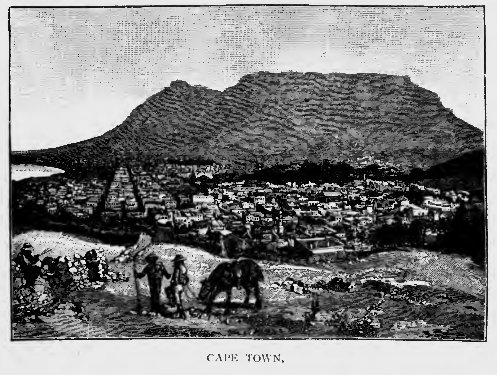

75 The Australian Colonies and South Africa

75 The British Empire

Chapter 76. Steps on the Path of Freedom.

76 The Growing Giant

76 The French Revolution and British Freedom

76 Freedom of the Individual: the Abolition of Slavery and the Slave Trade

76 Freedom of the Individual (continued): The Slavery of Toil -- Freeing the Worker

76 Freedom of Thought and Religious Opinion

76 Freedom of Communication -- The Steamboat and the Locomotive

76 Freedom of the Press -- Cheap Postage --The Electric Telegraph

76 Free Trade -- Freedom of Parliamentary Voting

76 The Improvement of Machinery

Chapter 77. Literature and Art Since 1714.

77 Writers and Artists of the Eighteenth Century

77 Edmund Burke

77 Cowper, Sheridan, Campbell, Lamb

77 Byron, Shelley, Keats, Burns, and Scott

77 The Lake Poets Southey, Wordsworth, Coleridge

77 Moore, Macaulay. -- The Writers of Our Own Time

Chapter 59. Anne -- The Last of the Stuarts. 1702-1714.

|

Principal events during the reign of Queen Anne: |

The Queen and her Councillors. (Ch 59)

"I am in such haste I can say no more but that I am very sorry dear Mrs. Freeman will be so unkind as not to come to her poor unfortunate, faithful Morley, who loves her sincerely, and will do so to the last moment." -- Queen Anne writing to the Duchess of Marlborough (1706).

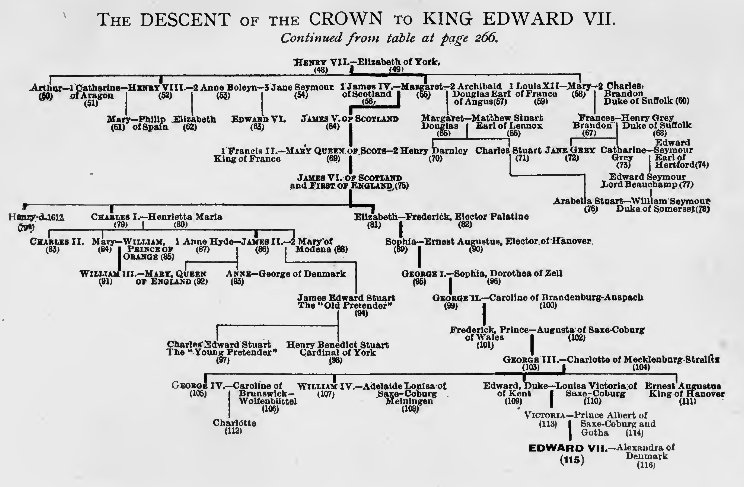

We now come to the reign of Queen Anne, the last of the Stuarts. In order to understand the events of this reign, it is necessary to remember exactly who Queen Anne was, and what was her claim to the throne. Anne was the second daughter of James II., and sister of Queen Mary, whose husband -- William of Orange, or William III. -- had just died. By the rule which had always been observed in England, the crown would by right have gone on the death of James II. to his son, James Edward, Prince of Wales.

But we have already seen how the leaders of the English Parliament had, by means of a "Revolution," altered the descent of the crown, and placed Mary upon the throne instead of her brother. Now that William and Mary were dead, and had left no children, those who had made the Revolution were determined that they would not lose the advantages which they had taken so much trouble to obtain.

In the last reign the Act of Succession had been passed which declared that the crown should only go to a Protestant, and everybody except the Jacobites now looked upon Queen Anne as the right and proper person to occupy the throne. But though everything went off peaceably, and the new queen was crowned without anyone objecting, it must not be forgotten that there were still in England a good many friends of the Jacobite cause, and that in Scotland and Ireland the Jacobites were far more numerous than in England. It was all very well for Englishmen to speak of the young prince as the "Pretender," and to declare that he was not even the son of James II., but as long as the "Pretender" could find friends ready to fight for him in England, and could rely upon the help of France, the most formidable of England's enemies, he was always a person to be feared.

The fact, too, that Queen Anne, like her sister, left no children to succeed her did much to strengthen the Jacobite cause, and, as the years passed by, the danger to those who had brought about the Revolution greatly increased. But the claims of the "Pretender" to the crown of England were not the only causes of trouble during Queen Anne's reign.

The division between the two great parties of Whigs and Tories had grown sharper than ever, and the quarrels and rivalries of the two parties became fiercer every year. The Whigs, who had been the real authors of the Revolution, were determined that they would keep in their own hands all the power which their success had brought them. At home it was their object to limit the power of the Crown and to strengthen that of the ministry. Abroad they were determined to continue the war which William III. had begun.

The Tories, on the other hand, were ready to give more power to the king or queen than were the Whigs. Their chief supporters were to be found among the members of the Established Church. They did not like the war, and were constantly trying to put a stop to it. They had been willing to support King William when James was alive, and they were ready to support Queen Anne as long as she lived, but they had no great love for the next heirs to the crown, namely, the Electress Sophia and her son George; and many of their leaders would rather have seen the "Pretender" made king than allow the Elector of Hanover to be put upon the throne by the Whigs.

We have already seen how Queen Anne had quarrelled with her sister Mary, and how the cause of the quarrel had been Mary's dislike for the Duchess of Marlborough. Now that Anne was queen it was not wonderful that her friend the duchess should become a very powerful person. Indeed, at the beginning of the reign the two most powerful people in the whole of England were, without doubt, the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough. Before she came to the throne Anne had found most of her friends among the Tories, of whom Marlborough was one, and it was to the Tories, therefore, that she looked for her advisers. A ministry was formed, of which Lord Godolphin, a son-in-law of the Duke of Marlborough, was the head, and nearly all the Whigs were turned out of office.

But on one very important point the Duke of Marlborough differed from the other advisers of the Queen. Marlborough was a soldier, and both as a soldier and as a statesman he wished to continue the war with France, and, as a soldier, no doubt he was ready to go on fighting battles in which he felt sure that he could earn glory and distinction. But as a statesman he wished to continue the war for another reason: he believed that if Louis XIV. of France were once allowed to become the master of Europe, it would not be long before he would also be master of England, and he felt therefore that it was most important that the whole power of England should be used to help those who were in arms against the French king.

The War with France. (ch 59)

"He is a soldier fit to stand by Caesar,

And give direction."

Shakespeare: "Othello," Act II., Scene 3.

Space does not permit us to go into all the particulars of the great war which raged in Europe during the reign of Queen Anne, but it would be quite impossible to tell the story of the reign without saying something about the war, for its consequences are to be felt and seen at the present day.

The war is known as the "War of the Spanish Succession," and it was so called because one of the chief reasons for which it was said to be fought was to fix the "Succession to the throne of Spain." King Louis of France wished to make his grandson King of Spain; the enemies of France were determined that this should be prevented, or that, if it could not be prevented, it should at least be declared that, whatever happened, the same person should never be both King of France and King of Spain. We have only got to look at the map of Europe to see how dangerous it would have been to any country which happened to be on bad terms with France, if the King of France had been master, not only of his own broad dominions, but also of the great Spanish peninsula which shuts in the western end of the Mediterranean Sea.

But though the quarrel about the Spanish crown gave its name to the war, the war was really fought by the people of England, Holland, and some of the German States to protect themselves from the powerful and ambitious King of France. Louis XIV., without doubt, fought for glory and the love of conquest, and Marlborough was right when he advised the queen that it was the duty and interest of England to help those who fought against King Louis.

At the beginning of Queen Anne's reign, so great was the power of Marlborough, and so great was his influence over the queen, that, though Marlborough himself was a Tory, though the queen was a friend of the Tories, and though her ministers were Tories, the duke succeeded in persuading both the queen and her ministers to go on with the war, and by so doing, to please the Whigs.

The war itself must always be memorable in the history of England. For the first time since the use of gunpowder became general, an English commander showed himself to be a real master of the art of war. It may probably be said with truth that the Duke of Marlborough was the greatest general this country ever produced, and his greatness as a soldier was recognised, not only by his own countrymen, but by every nation in Europe, whether friend or foe. The French feared him, and his name became a household word in France, where young and old caught up the tune of the famous song, "Marlbrook s'en va-t-en guerre." ["Marlbrook sen va-t-en guerre," translated "Marlbrook has gone to the wars". The air is still very well known to us in England under the title of "We won't go home till morning," with the familiar chorus of "He's a jolly good fellow."]

The Dutch and the Protestants of Germany, however jealous they might be of a foreigner, agreed to place the duke at the head of their armies, knowing that he, and he alone, could lead them with success against the experienced generals of Louis XIV.

Indeed, the genius of Marlborough showed itself almost as much in his dealings with the Dutch and German generals with whom he had to act, as in the skill with which he led his armies into battle. The Dutch leaders especially, slow in their movements, jealous of interference, and often mistrusting their English allies, gave the duke the greatest trouble, and it was only by patience, by skilful flattery, and by persuasion -- sometimes accompanied by bribes -- that Marlborough was able to keep together the mixed army under his command.

One great man, however, proved to be an exception to the general rule. In Prince Eugene of Savoy, Marlborough found a skilful and devoted ally, on whom he could always depend, and from whose jealousy he had nothing to fear.

The Triumph of Marlborough. (ch 59)

"Great praise the Duke of Marlborough won." -- Southey: "After Blenheim."

The first battle in the war was a surprise to all Europe. The French armies, so long victorious, were considered almost invincible. The French generals were reckoned to be the most experienced and the most skilful in Europe. Great, therefore, was the rejoicing in England when the news arrived that on the 13th of August, 1704, the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene had totally defeated a great French army at Blenheim, a village lying on the river Danube, in Bavaria.

Two years later another great victory at Ramillies, in Belgium (May 23rd, 1706), compelled the French to withdraw from the Netherlands. A victory by Prince Eugene at Turin, in the north of Italy, drove the French out of that country. On every side Louis, so often victorious, saw himself defeated. But France was then, as she is now, too great and strong a nation to be really beaten in a single campaign.

The year after the victory of Ramillies the French gained several successes over the Allies, and in the following year (1708) an expedition was again prepared for the purpose of bringing over the "Pretender" and invading England. Happily, the "Pretender" fell ill, and the expedition came to nothing. But it was plain that the war must be continued. Marlborough once more took the command, and on the 11th July defeated the French at Oudenarde, a town on the river Scheldt, in Holland, and the victory was followed by the siege and capture of the strong fortress of Lille (9th December, 1708).

In 1709 the last and fiercest of the four great battles in which Marlborough proved victorious was fought at Malplaquet, in Belgium (September 11th). The losses on both sides were very great, that of the Allies amounting to no less than 20,000 men.

The victories of Marlborough will always be remembered -- and justly remembered -- by the people of England. They were the means of preserving our country and the other Protestant States from being crushed by the great military power of France. Our free government and our present line of sovereigns are among the results which we owe to the genius of Marlborough and the bravery of his troops. The names of "Blenheim" and "Ramillies" have long been kept alive in the Royal Navy, and to this day are borne by two of the most powerful of our warships.

But there was one other victory won in the same year as that in which the battle of Blenheim was fought, which, though it was gained with little fighting and little loss, has left us a prize almost as great as that which Marlborough's splendid campaign secured.

We have on the opposite page a picture of the noble outline of the Rock of Gibraltar, the huge fortress which guards the western entrance to the Mediterranean, and on the highest point of which the flag of Britain flies. It was in the year 1704 that Admiral Sir George Rooke, being with his fleet in the Mediterranean, attacked, and captured almost without resistance, the fortress of Gibraltar, then in the hands of the Spanish allies of Louis XIV.

From that day to this, Gibraltar has remained in British hands. For many years it guarded the Straits, and was the most important fortress in all the British Empire. It remains as a great monument of our success in the days of Queen Anne, and it may one day become again as important and valuable a fortress as it was in days gone by. [The fortress of Gibraltar, having been taken by Sir George Rooke in 1704, was ceded to Great Britain by Spain by the Treaty of Utrecht, signed in the year 1713.]

The Tories in Office. (ch 59)

"When royal Anne became our queen,

The Church of England's glory,

Another face of things was seen,

And I became a Tory."

"The Vicar of Bray," written 1720.

But while Marlborough had been so successfully carrying on the war abroad, his position at home had been growing weaker and weaker. The Tories, as we have seen, disliked the war from the very beginning, and it was only Marlborough's great influence with the queen which had enabled him to carry it on at all.

Gradually the duke found that his old friends were leaving him, and that the Tories in the House of Commons lost no opportunity of making attacks upon him. This naturally led him to make friends with the Whigs, who he knew would support him in carrying on the war. In the year 1707 he persuaded the queen to call several of the Whigs into the ministry. A few of the Tories, among whom were Harley, afterwards known as Earl of Oxford, and St. John, afterwards known as Lord Bolingbroke, remained in the ministry. But it has always been found difficult for a Government to succeed when its members are not really agreed, and it soon became clear that the Whigs and Tories in the new Government were not agreed.

Harley was the first to see that the time had come when the power of the Duke of Marlborough over the queen might be destroyed. Marlborough's power had come through his wife, and his enemies now tried to destroy it by the same means. Queen Anne had made a new favourite, Miss Abigail Hill -- or Mrs. Masham, as she became -- cousin of the duchess.

The new favourite lost no opportunity of stirring up the queen's displeasure against her old friend, "Mrs. Freeman," by saying all the evil she could of the Whigs, and praising the Tories. The queen, who was really a very strong Tory, readily listened to these attacks, the more so as she had long been tired of the bitter tongue and quarrelsome temper of the Duchess of Marlborough. From this time the fate of Marlborough was sealed, and it was not long before his enemies succeeded in bringing about his downfall.

The favour of the queen having once been won by Mrs. Masham, and lost by the duchess, the disgrace of Marlborough and of the Whigs on whom he now relied as his best supporters in carrying on the war, was only a question of time. The downfall was hastened by an event which took place in London, and which stirred up the people as well as the queen against the Whigs.

This event was the trial of a clergyman named Dr. Sacheverell. It was a small matter in itself, but men's minds were so excited that it led to important consequences. Sacheverell was a Tory, and a clergyman of the Established Church. He preached a sermon at St. Paul's, in which he spoke in favour of the Divine Right of Kings, and of the duty of their subjects to obey them, whatever they said or did.

The Whigs were angry with Sacheverell, for they said that such teaching was an attack upon the Revolution, and upon the law as it had been settled by the Revolution. So angry were the Whigs that, instead of putting Sacheverell on his trial in the ordinary way, they went so far as to bring an "impeachment" against him.

As a result, Sacheverell was forbidden to preach for three years, but the attack which had been made upon him was looked upon by all the Tories as an attack upon the Church; and as the Church was a great power, and very popular in the country, a strong feeling was aroused against the Whigs. There were fierce riots in London, and some of the chief Whig ministers were driven out of office. A new Parliament was summoned, in which the Tories had a majority, and Harley, leader of the Tories, was made Prime Minister.

The Fall of Marlborough. (ch 59)

"Marlbrook, the prince of commanders,

Has gone to the wars in Flanders;

His fame is like Alexander's,

But when will he ever come home?"

Song: "Marlbrook."

Now that the Tories were in power, it was clear that the war which they had so long disliked would be brought to an end, and that, in order to put a stop to the war, Marlborough must first be dismissed from his office.

The queen, who was strongly on the side of Harley and the new ministers, dismissed the Duchess of Marlborough from Court, took away from her all her offices and honours, and refused to see her. Harley was made Earl of Oxford, as a sign of the queen's favour, and terms of peace were proposed to King Louis.

Marlborough now came back to England, to find that not only was the war in which he had earned so much distinction to come to an end, but that he himself was to be disgraced and deprived of his command. A whole set of charges was brought against him. It was declared that he had made a dishonest use of the money which had been voted by Parliament for the purpose of carrying on the war. He was dismissed from his command, and the Duke of Ormonde, who was suspected of being a Jacobite, was put at the head of the army.

Only one more thing remained to be done to bring the war to an end. The majority of the House of Lords had up to this time been friendly to the Whigs and to Marlborough. It was necessary to get the consent of the House of Lords as well as that of the House of Commons. By the advice of the Earl of Oxford twelve new peers were created for the purpose of giving the Tories a majority in the House of Lords as well as in the House of Commons.

All was now ready for the last step to be taken, and on the 31st of March, 1713, a peace was signed at Utrecht, in Holland, by which the long struggle between England and France was for a time ended. The terms of the peace were not favourable to England, whose armies had been so successful throughout the war. But there can be little doubt that among the ministers who made the peace there were some who were traitors to the country which they pretended to serve. It is known that one of them -- St. John, afterwards Lord Bolingbroke -- was at this very time plotting for the return of the "Pretender"; and it is believed that Harley, Earl of Oxford, was also trying to make terms with the "Pretender," so that he might have a friend in case the Stuarts should, after all, come to the throne again.

It was not wonderful, therefore, that a ministry whose members were actually plotting with the enemy should not have been very earnest in standing out for the interests of England.

But though the Peace of Utrecht was not very favourable in its terms to this country, it gave us three important possessions -- namely, the island of Minorca, in the Mediterranean, the fortress of Gibraltar, and the island of Newfoundland, all of which had been claimed by our enemies, but which were now admitted to belong to Great Britain. Minorca has been lost, but Gibraltar and Newfoundland are still part of the British Empire.

The Last of the Stuarts. (ch 59)

"Be it enacted that The succession of the Monarchy of the United Kingdom of Great Britain, and of the Dominions thereto belonging, after her Most Sacred Majesty, and in default of issue of her Majesty, be, remain, and continue to the Most Excellent Princess Sophia, Electress and Duchess Dowager of Hanover, and the Heirs of her Body being Protestants, upon which the Crown of England is settled by an Act of Parliament made in England in the twelfth year of his late Majesty King William the Third." -- 5 Anne, Cap. VIII., Art. 2.

The queen's health was now fast failing, and it was clear that she had but a short time to live. She had no child to succeed her, and for a time the country was in real danger of a return of the "Pretender." St. John, now Lord Bolingbroke, who had become Anne's most trusted minister, would certainly have called back the Stuarts on the queen's death if he had been allowed to do so.

But the greatness of the danger alarmed the Whigs, and they decided to act at once while there was time. The Duke of Argyle and the Duke of Somerset made their way to the palace of Kensington, where the queen lay dying. As members of the Privy Council, they had the right to an audience of the sovereign at any time. They now claimed their right, and were brought into the chamber of the dying queen. They told her plainly what was the danger which threatened the country, and how the Protestant cause, of which she had been during her life the great supporter, would be ruined if the Act of Succession were not obeyed, and if the Elector of Hanover were not made king upon her death.

There was one way, and one way only, they declared, by which the "Pretender" could be prevented from returning, and that was to appoint Whig ministers, who would insist upon the Act of Succession being obeyed. Anne listened to these counsels, and agreed to them. She gave the "White Staff," which was the sign of office, to the Duke of Shrewsbury, and made him Lord Treasurer, or head of the Government. The cause of the Protestant Succession had been saved. The new Whig ministers immediately sent a message to the Elector George, bidding him come over with all speed to England, and they made preparations to receive him and to put down any resistance which might be offered.

On the 1st of August, 1714, Queen Anne died, in the fifty-first year of her age and the thirteenth year of her reign. With her ended the line of the Stuart Sovereigns, which began with her great-grandfather, James I.

The Union with Scotland. (ch 59)

"The union of lakes -- the union of lands--

The Union of States none can sever--

The union of hearts -- the union of hands--

And the flag of our Union for ever!"

G. P. Morris: "The Flag of our Union."

A great part of the pages which contain an account of Queen Anne's reign has been taken up with the story of wars on the Continent and disputes between the two great parties at home. There was, however, one important event which took place in this reign which was brought about without war, and about which the two great parties for once managed to agree. This event is such an important one, and has had such a great and lasting influence upon our history, that it must be specially mentioned.

It was in the year 1707, the sixth year of the reign of Queen Anne, that the Act of Union between England and Scotland was passed. It may be asked, What need was there of any Act of Union between the two countries now that they both had the same Sovereign? But we have read enough in this book to make it quite clear that, though the crown of England and the crown of Scotland were both worn by the same king or queen, there was as yet very little real union between the two countries. On the contrary, there had been perpetual disputes and constant fighting, and the English Parliament and the Scottish Parliament had not only been quite distinct bodies, but had been strongly opposed to one another.

At the beginning of Queen Anne's reign there was a very angry feeling in Scotland against the English Government. A large number of people in Scotland, moved by the persuasions of a man named Paterson, had joined together to send out an expedition to the Isthmus of Darien, the narrow strip of land which divides the Atlantic from the Pacific and which connects the continents of North and South America. Those who joined in the expedition believed that Darien would become a great and powerful colony, and that its possession would bring great wealth and strength to the kingdom of Scotland.

The English Government, however, looked upon the expedition with little favour. They knew that it was sure to rouse the anger of the Spaniards, and would probably bring about a war which would injure English trade. The Spaniards did, in fact, attack the Scottish colonists. The colonists were defeated and ruined, and the whole expedition ended in total failure and in the loss of very large sums of money.

The Scots, smarting from their loss, declared that the English Government had destroyed the expedition, and the feeling against England became very bitter. The Scottish Parliament set to work to thwart the English ministers. They refused to pass an Act of Succession declaring that the Princess Sophia and her heirs should succeed to the throne of Scotland, and they showed themselves unfriendly in many other ways.

The English ministers prepared to punish the Scots for their unfriendliness. A Bill was actually brought into Parliament declaring that all Scotsmen should be looked upon as foreigners in England, that heavy duties should be levied upon goods crossing the Border from Scotland; and orders were given that troops should occupy the Border fortresses as if Scotland were already an open enemy. The Scots were now in their turn alarmed by the threats of their powerful neighbour, and, happily, wise counsels prevailed.

There was already a large party in both countries which desired to see a real union between England and Scotland, and steps were now taken to carry the wishes of these parties into effect. Commissioners were appointed by the Parliaments of the two countries to arrange the terms on which the Union should take place.

There was a great deal of "give and take" on both sides, but on the whole the terms were very favourable to Scotland, the weaker country. So favourable were they that in January, 1707, the Act of Union passed the Scottish Parliament by a majority of 41 in a house of 179 members. It had now only to pass through the English Parliament; and so skilful were the ministers in placing the matter before the two Houses that, despite the bitter feeling between Whigs and Tories, the Act was passed with scarcely any opposition, and became from that time the law of the land.

The first article of the Act is in these words: "That the Kingdoms of England and Scotland shall upon the First day of May, which shall be in the year One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seven, and for ever after, be united into one Kingdom in the name of Great Britain; and that the Ensigns Armorial of the said united Kingdom be such as her Majesty shall appoint, and the Crosses of George and Andrew be conjoined in such manner as her Majesty shall think fit, and used in all Flags, Banners, Standards and Ensigns, both at sea and land." [5 Anne, chap. v., art. I.]

The following are the principal points in the Act of Union between England and Scotland:

(1) The kingdoms of England and Scotland were to become one kingdom, under the title of "Great Britain."

(2) The Flags of the two countries were to be joined together. The Red Cross of St. George with the White Cross, or Saltire, of St. Andrew.

(3) The Parliaments of England and Scotland were to be united, and the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain was to sit thenceforward at Westminster.

(4) There were to be forty-five Scottish members in the House of Commons.

(5) Sixteen of the Scottish peers were to be elected by the votes of all the peers of Scotland, and were to take their places in the House of Lords. All peers created by the Crown in future were to be peers of the United Kingdom, and not of England or Scotland.

(6) Scotland was to take its share in bearing the debt of England, but a large sum (£398,000), was to be paid by England to discharge the debt of Scotland and to repay the losses of those who had suffered from the failure of the Darien expedition.

Such were the main points of this great Act of Parliament which has thrown open to Scotland the wealth and resources of England, and has given to its people a full share in the great naval power of the southern kingdom; an Act which, on the other hand, has given to England the energy, the courage, and the enterprise of Scotsmen, who have taken their full share in founding, strengthening, and keeping that great British Empire to which both Englishmen and Scotsmen are proud to belong.

Chapter 60. Constitutional History of the Stuart Period.

Magna Charta Re-enacted. (ch 60)

"And we will, that if any judgment be given from henceforth, contrary to the Points of the Charter aforesaid * by the Justice, or by any other of our Ministers that hold Pleas before them against the Points of the Charters, it shall be undone, and holden for nought." 25 Edward I., Chap. II.

[*Magna Charta and the Charter of the Forest.]

If we look back over the history of the Stuart Period, and ask ourselves for what it ought chiefly to be remembered, we shall probably say that it is to be remembered as a time when very great and important changes were made in the form of government of this country. It may be called, therefore, a period of great "Constitutional changes." If we have read the chapters which have gone before with care, we shall already be familiar with these changes, which are described in their proper places as they occurred.

But it will, perhaps, make it easier to recollect what the changes were, and to understand their true importance, if we collect them together into a chapter by themselves. At the end of the Tudor Period we found Queen Elizabeth reigning as an almost absolute sovereign, Parliament with scarcely any real power, and the queen taking the foremost part in everything which concerned the government of the country. The Divine Right of kings to rule was accepted as a truth which could hardly be questioned, and with the Divine Right of kings to govern there had also come "the right divine of kings to govern wrong."

When the Stuart line came to an end on the death of Queen Anne, all these things had changed. Parliament had become all-powerful. The Divine Right of Kings was an exploded idea in which only a few old-fashioned Jacobites believed. The sovereign still took some part in governing the country, but a much less active part than in Tudor days. It was the king's ministers who really carried on the business of the country, and who were responsible for the success or failure of the king's government.

Such were the principal changes which had been made during the 111 years of which we have been reading. As we know, there had been many struggles before the new state of things could be brought about or be made part of the law of the land. More than four hundred years before Charles I. came to the throne, Magna Charta had declared that taxes should not be raised without the consent of the Council of the kingdom, and that no one should be imprisoned without cause and without trial by his peers. But though the Kings of England had over and over again confirmed the promises made in Magna Charta, it was still found necessary, in the time of the Stuarts, to fight for those very liberties for which the Barons had contended under Stephen Langton.

It was to insure that the promise made in Magna Charta should not any more be broken that the "Habeas Corpus Act" was passed in 1679. The Habeas Corpus Act made it absolutely illegal to detain a prisoner in gaol without trial; and, what was more, it made every person whose duty it was to carry out the law fear the consequences which would befall him if he did not do his duty.

To this day the Habeas Corpus Act is acknowledged to be one of the greatest protections which a British citizen enjoys. If a person be imprisoned or detained in custody without proper trial or legal authority, the prisoner or his friends may apply to any judge, or to any one of a number of persons named in the Habeas Corpus Act, for a writ of Habeas Corpus directing the person who has charge of the prisoner to bring him up for trial. The judge dare not refuse to order the writ to be issued, for, by the Act, he may be severely punished if he does so. The person to whom the writ is sent dare not disobey it. He is bound to bring up his prisoner for trial, and knows that he, too, will be severely punished if he does not immediately obey.

The Petition of Right and the Bill of Rights have made it clear that it is contrary to the law for the king or queen to keep up a standing army in this country in time of peace, without the consent of Parliament. There can, therefore, no longer be any danger of the Crown raising an army to put down Parliament or to oppress the people.

By the same Act it has been made illegal for the Crown to raise taxes without the consent of Parliament.

Responsibility of Ministers -- The "Cabinet." (ch 60)

"The king can do no wrong."

The formation of the "Cabal" Ministry in the time of Charles II. was an important event, because it led to the plan of governing by a Cabinet Council, which is now the way in which the government of our country is carried on. The Cabinet is a small committee of from twelve to eighteen members chosen from amongst the ministers of the Crown. The Cabinet conducts its councils in secret, and it decides what shall be the policy of the Government in all matters. It is the Cabinet Council which really governs the United Kingdom, and which plays a very important part in governing the whole of the British Empire.

It is to the Revolution that we owe government by party and the responsibility of ministers. We have just said that the Cabinet really governed the country, but the Cabinet is appointed from among the members of one party only, and it is from the party which has the majority in the House of Commons that the Cabinet is chosen. So it is really true, in a sense, to say that it is a party that governs the country.

Together with party government came, very naturally, Responsibility of Ministers. When once it became clear that the Government must change every time the majority in the House of Commons changed, the king or queen could not be expected to be made answerable for things that were done by both parties. The Whigs invented a plan which got over the difficulty. They said, "It is the duty of the king or queen to rule only with the advice of his or her ministers. As long as the sovereign follows the advice of ministers, the ministers, and not the Crown, shall be responsible for all that is done." In order to insure this plan being faithfully followed, it was decided that a minister's name should always be signed after that of the sovereign, so that all the world might know who was responsible for any particular act.

Here is an example of King Edward's signature, which will show what is meant:

"Edward, R.F.

"Given at Our Court at St. James's, this Eighth Day of July, One Thousand Nine Hundred and One, and in the First Year of Our Reign.

"By His Majesty's Command.

-- "George Hamilton."

In books about the "Constitution" of England we often find it said that "the king can do no wrong." It is not hard, after what we have just read, to understand what this means. It means that if a wrong thing be done by order of the king or queen, the whole blame must be thrown upon the minister by whose advice the thing has been done, and not upon the sovereign. The sovereign does right to act according to the advice of the minister; the minister does wrong in giving the sovereign bad advice. Hence "the king can do no wrong."

The House of Commons and the People of England. (ch 60)

"So may it ever be with tyrants." [A translation of a famous Latin phrase. "Sic temper Tyrannis."]

We have spoken in many of the preceding chapters of what was done by Parliament and by the House of Commons. We should not, however, understand the history of Stuart times rightly if we believed the House of Commons to have been the same kind of body that it is now. In the time of the Stuarts, the members of the House of Commons were elected by a very small number of the people of England, and, in many cases, members were not really elected at all, but were appointed to their seats by the king or by some great lord.

In several instances, the right to sit in Parliament for a particular place was looked upon as belonging to a particular family. There was no such thing as an election such as we see nowadays, in which nearly every man in town or country has the right to give a vote. It was only in some of the large towns that there was anything like a modern election.

It must not be supposed, however, that, despite all these differences between the House of Commons in the time of the Stuarts and the House of Commons in our own day, the majority in the House did not often represent the real feeling of the majority of the people of England. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that on many occasions the House of Commons did not at all represent the majority of the people of England, but only the views of a very small class in the country.

As to the Revolution itself, to which we owe so much, it was begun and carried out, not by the people of England, nor, indeed, by the House of Commons, but by a few wealthy and powerful men, most of whom sat in the House of Lords. It is probable that much of what was done by the great lords who brought about the Revolution was done with selfish views. At the same time, it must be admitted that there were among these great lords, and those who supported them, many who really risked their lives and their fortunes in support of the cause which they believed to be the cause of liberty. They fought to bring about a change which they truly thought was necessary for the safety of their country, its religion, its laws, and its liberties. The United Kingdom certainly owes a great debt to the makers of the Revolution of 1688.

Nor must we forget to speak of the great Constitutional change which was made in the reign of the last of the Stuarts namely, the "Union" between England and Scotland, and the creation of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain.

One or two other points ought to be noticed in a chapter which speaks of the Constitutional lessons which are to be learnt from this period. The history of the period teaches us very plainly that Tyranny, under whatever name, is hateful to the English people.

They fought against King Charles and allowed him to be put to death because he acted like a tyrant. They allowed the House of Lords to be destroyed because it supported King Charles; but when the House of Commons, which then became sole master of the nation, acted like a tyrant, the country gladly saw the members of the House of Commons driven into the street by a party of musketeers. And once more, when the Army which had got rid of the Parliament, sought in its turn to ride roughshod over the people of England, the people of England, with one voice, declared that military tyranny was as bad as the tyranny of a king or the tyranny of a Parliament.

Nor did Englishmen rest contented until they had built up for their country a steady, reasonable form of government, in which every part of the nation took its share, and in which the tyranny of either king, Lords, Commons, or Army was, as they believed, made impossible.

Chapter 61. Literature in the Stuart Period

Milton, the Puritan Poet. (ch 61)

"Milton, thou shouldst be living at this hour;

England hath need of thee: she is a fen

Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

Have forfeited their ancient English dower

Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

Thy soul was like a star, and dwelt apart:

Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea;

Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free;

So didst thou travel on life's common way,

In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

The lowliest duties on itself did lay." -- Wordsworth.

In the next two chapters will be found a very short account of some of the great writers who lived during the Stuart Period. It is a good thing to know something about the life of a great poet or a great prose-writer, and to understand something of the time in which he lived and of the part which he played during his lifetime. Every writer, whether he be a poet or a writer of prose, owes a great deal of his thoughts to the things which he sees going on around him and to the circumstances in which he himself lives. The very language which he uses is but the repetition in a beautiful or in an orderly form of the words which he hears around him in his daily life.

But the real way to know a great author is to read his books; and no one should pretend to know anything about Milton, Dryden, or Addison, or any other great authors, until he has read the works which made those authors famous. But though in a book like this we cannot read the actual poems of Milton, of Dryden, or of Addison, we can, at any rate, learn who the writers were; and when we read "Paradise Lost" "Alexander's Feast," or the "Spectator," we shall be much better able to understand what we read, and to follow the meaning of many things which would otherwise puzzle us. We shall learn also why the language used by Dryden is so different from that used by Milton, and why the language of Addison is, in its turn, so different from that of Dryden.

In speaking of John Milton, first of all the great writers of the Stuart Period, we must not forget that even a greater poet than he actually lived for several years in the Stuart Period, and that Shakespeare, who died in the year 1616, not only lived thirteen years under King James's rule, but that some of his most famous plays, such as "The Tempest" "Macbeth," and "King Lear" appeared during the reign. But we have already spoken of Shakespeare in the story of the Tudor Period, and it was right to do so, for the thoughts and the language of Shakespeare were the thoughts and the language which he had learnt to use during the reign of the great queen to whom he paid so many compliments in his poems. Shakespeare is usually called an Elizabethan writer, and such he really was.

The same thing may be said of the writings of Bacon, who, as we know, lived through the reign of James I. and on into the reign of Charles I., and of whose best-known works "The Advancement of Learning" (1605) and the "Novum Organum" (1620) appeared during the reign of James I. His writings and his thoughts really belong to the time of Elizabeth more than to the century which followed her death, and it is for that reason that the writings of Bacon, as well as the writings of Shakespeare, have been mentioned in the story of the Tudor Period, and are not spoken of at any length in this Part, which deals with the Stuart Period.

If it were asked who was the most famous English writer of the seventeenth century, few people would have any doubt as to the answer. All would agree in giving the name of John Milton. Milton was born in the year 1608, in London. He was the son of a scrivener, or writer of legal documents. He was educated at St. Paul's Grammar School, and went to college at the University of Cambridge. Throughout his life he took the side of the Puritans, and he was on several occasions employed by the government of the Commonwealth to fill public offices. He was made Secretary to the Council which was appointed to carry on the government in the year 1649, the first year of the Commonwealth.

At the Restoration he fell into great misery, for he was one of the few supporters of the Commonwealth who were specially excepted by name from the pardon given by the king to those who had taken part in the war. He was imprisoned, and, to add to his misfortunes, his sight -- which he had injured by overstudy when he was a young man -- gradually failed him, and he became quite blind. Towards the end of his life he was released, and lived in poverty and retirement till the year of his death, in 1674. He died at the age of sixty-six, and was buried in St. Giles', Cripplegate; his monument may be seen in the Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey.

It is not, however, as a politician that Milton is remembered, but as one of the greatest of England's poets. Milton was a Puritan, who lived among the Puritans, heard their speech, and understood their thoughts. It was natural, therefore, that in his poetry he should speak of religion, which formed so great a part of the life of the Puritans, and that the language he used should frequently be taken from the Bible, from which the Puritans so often quoted, and which they held so dear.

But Milton was also a scholar who had been educated at the University of Cambridge. He had learnt Latin and Greek, and was familiar with the writings of the great Greek and Latin authors. It is not strange, therefore, that in his poetry we should find many words and thoughts which are taken from the Bible side by side with many which are taken from the writers of Greece and Rome.

In his beautiful poem of "Lycidas" Milton uses a Greek name to describe the subject of the poem -- his friend Edward King, who was drowned at sea. The poem is a lament over the unhappy death of his friend, and in almost every line of it we find names and thoughts and words which are taken from the old Latin poets, and which can only be properly understood by those who have read something of the writings of Roman authors. Here are a few lines taken from the poem to show how true this is:

"For Lycidas is dead, dead ere his prime.

Young Lycidas, and hath not left his peer:

Who would not sing for Lycidas? He knew,

Himself, to sing, and build the lofty rhyme.

He must not float upon his watery bier

Unwept and welter to the parching wind,

Without the meed of some melodious tear.

Begin, then, sisters of the sacred well

That from beneath the seat of Jove doth spring:

Begin, and somewhat loudly sweep the string;

Hence with denial vain, and coy excuse:

So may some gentle muse

With lucky words favour my destined urn;

And, as he passes, turn,

And bid fair peace to be my sable shroud.

For we were nursed upon the self-same hill,

Fed the same flock, by fountain, shade, and rill."

The "Sisters of the sacred well" are the "Muses" who the ancients believed were the Goddesses of the Arts, and especially of Poetry. Jove, or Jupiter, was the great king and chief of all the gods of Greece and Rome.

Again, the beautiful lines which speak of the uncertainty of life and the suddenness of death can only be understood by those who know the ancient story of the Greeks and Romans that the life of man is a thread spun by one of the "Fates" and that as Clotho, the spinner, spins the thread, her sister Atropos stands beside her with a pair of shears in her hand and suddenly cuts the thread, and thereby ends the life of a man. Atropos is "The fury with the abhorred shears" who "slits the thin-spun life." But in this poem of "Lycidas," and still more in others of his great poems, are to be found proofs that Milton was a great reader of the Bible. One of his most beautiful and well-known poems is the Christmas hymn which begins with the lines

"This is the month, and this the happy morn

Wherein the Son of Heaven's Eternal King

*****

Our great redemption from above did bring."

This poem was written in 1629, when Milton was a young man of twenty-one years.

But it was in his old age, when his sight had left him, that Milton wrote his greatest poem, called "Paradise Lost." In "Paradise Lost" is told the story of the creation of man, of his sin in the Garden of Eden, and of his punishment. The poem describes the story as it is told in the book of Genesis in the Old Testament. It is a noble and beautiful work, full of great thoughts, and of lines which have become famous wherever the English language is known.

It is not all of equal interest, because parts of it are taken up with describing the religious quarrels of the times, quarrels which were of great interest to Milton, a strong Puritan, and a man who had taken part in the Rebellion, but which are not of such great interest now. There is, however, a great deal of "Paradise Lost" which is still of the deepest interest to all who read it. Few lines in the whole poem are better known than those which end the story, and tell how Adam and Eve, driven forth from the Garden of Eden by the angel with the fiery sword, made their way together into the world beyond.

"They, looking back, all the eastern side beheld

Of Paradise, so late their happy seat,

Waved over by that flaming brand; the gate

With dreadful faces throng'd, and fiery arms.

Some natural tears they dropt, but wiped them soon;

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their Guide:

They, hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow

Through Eden took their solitary way."

Among the other famous poems of Milton we may remember his "L'Allegro," a poem singing the praises of mirth and innocent pleasure, and "Il Penseroso," a poem on melancholy.

Puritan Prose-Writers. (ch 61)

"An' thus it was: I, writing of the way

And race of saints in this our Gospel day,

Fell suddenly into an allegory

About their journey and the way to glory."

-- Bunyan's Apology for his Book.

JOHN BUNYAN.

Another great Puritan writer of this period was John Bunyan, the famous author of The Pilgrim's Progress. He was born in 1628, in the reign of Charles I., and died in 1688, the last year of James II. He, like his father before him, had been a tinker, and lived in Bedfordshire. He was an honest, God-fearing man, learned in his Bible. He taught and preached repentance to his countrymen, but by his preaching he offended many persons, and was thrown into Bedford gaol. There he lay for three years, and it was while in gaol that he wrote the great allegory of "The Pilgrim's Progress," which has made his name so famous.

The book describes how "Christian," and "Faithful," and "Hopeful" journeyed on their way from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City; how Christian fell into the Slough of Despond; how he bore and at last lost the burden of his sins, which was heavy upon his back; how he was tempted in Vanity Fair, and was taken by Giant Despair at Doubting Castle; and how at last, after passing through The Valley of the Shadow, he crossed the River, and came to the Celestial City. The story is an allegory describing the life of a Christian man, his fight with evil, his trust in God, and his passage through death to Everlasting Life.

All these things, and many more, are told in the story of "Christian," "Faithful," "Hopeful," and "Christiana," Christian's wife. They are written in most pure and beautiful English, which every English man and woman, and almost every English child, can understand. Few books have ever been written in the English language which have been more widely read and better loved than John Bunyan's "Pilgrim's Progress." In 1672 Bunyan was released from prison. He died sixteen years later in London, in the year 1688.

THE TRANSLATORS OF THE BIBLE.

We must not forget, in speaking of the great religious writers of this time, to mention the Translators of the Bible, who have given us the familiar words of the Authorised Version. They shared with Milton and Bunyan the power of writing clear and beautiful English, which has remained part of our English language, and which will be remembered as long as English is read or spoken.

It was in the reign of King Charles II. that the simple and beautiful prayer which comes in the service for "Those at Sea" was written. This prayer, which is read every day on every ship in the Royal Navy, was added to the Prayer-Book in the time of King Charles II. It is heard, read, and repeated by many who are not in the habit of using the Church Prayer-Book, and part of it may be quoted here, for it refers to one of the greatest Institutions of our country.

"O Eternal Lord God, who alone spreadest out the heavens, and rulest the raging of the sea; who hast compassed the waters with bounds until day and night come to an end; Be pleased to receive into thy Almighty and most gracious protection the persons of us thy servants, and the Fleet in which we serve. Preserve us from the dangers of the sea, and from the violence of the enemy; that we may be a safeguard unto our most gracious Sovereign Lord, King Edward, and his Dominions, and a security for such as pass on the seas upon their lawful occasions."

Other Poets and Prose-Writers of the Early Stuart Period. (ch 61)

Protus the King speaks to the Poet--

"Thou leavest much behind, while I leave nought

Thy life stays in the poems men shall sing,

The pictures men shall study." -- Browning: "Cleon."

JOHN DRYDEN.

Among the great writers of the Stuart time must be mentioned the poet Dryden, who was born in the year 1631, when Charles I. was king, and who died in 1700, just before Queen Anne came to the throne. Dryden's poetry varies greatly, both in beauty and in interest. He wrote several long poems, such as "The Hind and the Panther" and "Absalom and Achitophel" which were really political poems, and referred to things which were going on at the time. The names, which were taken from the Bible, or from Latin or Greek stories, were really used to describe people who were alive at the time. Thus, in one of the poems just mentioned, Absalom is only another name for the Duke of Monmouth, Achitophel for the Earl of Sunderland. These political poems were of greater interest when they first appeared than they are now, but there are in them passages which are very finely written, and which will always be remembered.

They also contain many short, witty phrases which have never been forgotten. Such is the well-known description of the false patriot in the lines which tell us of the man who--

"Usurped a patriot's all-atoning name.

So easy still it proves in factious times

With public zeal to cancel private crimes."

Dryden also wrote many poetical translations of the old Latin poets, but it is by some of his shorter poems that he will always be best known. Of these the most famous are the splendid poems, "The Ode to St. Cecilia," and "Alexander's Feast" or the "Power of Music," which begins with the lines--

"Twas at the royal feast for Persia won

By Philip's warlike son:

Aloft in awful state

The godlike hero sate

On his imperial throne;

His valiant peers were placed around;

Their brows with roses and with myrtles bound

(So should desert in arms be crowned).

The lovely Thais, by his side,

Sate like a blooming Eastern bride,

In flower of youth and beauty's pride.

Happy, happy, happy pair!

None but the brave,

None but the brave,

None but the brave deserve the fair."

The last lines of the poem -- in which the coming of St. Cecilia, the Inventress of the "Organ," is described -- are very familiar:

"Thus long ago,

Ere heaving bellows learned to blow,

While organs yet were mute,

Timotheus, to his breathing flute

And sounding lyre,

Could swell the soul to rage, or kindle soft desire.

At last divine Cecilia came,

Inventress of the vocal frame;

The sweet enthusiast, from her sacred store

Enlarged the former narrow bounds,

And added length to solemn sounds,

With Nature's Mother-wit, and arts unknown before.

Let old Timotheus yield the prize,

Or both divide the crown;

He raised a mortal to the skies,

She drew an angel down."

CLARENDON.

(B. 1608, d. 1674.)

We must turn now from a great poet to a great writer of prose namely, the Earl of Clarendon whose name has already often appeared in these pages, and whom we know as a minister and as a politician. It is, however, as a writer of the "History of the Rebellion" that Clarendon is most justly famous. In that great book, not only does he give us a full and interesting account of the stirring events which happened during his lifetime, and in which be himself took no small part, but he has there drawn for us a number of pictures of Englishmen whom he knew which will always remain as wonderful examples of clear and beautiful writing and of lively description.

We have already read the descriptions which Clarendon has given us of two men whom he knew -- the one Falkland, a dear friend, and the other, Blake, a political enemy. We will here only quote one more passage taken from the same description of Lord Falkland.

This is how the historian closes his account of the life of the gallant young soldier who fell fighting at the battle of Newbury: "Thus fell that incomparable young man, in the four-and-thirtieth year of his age, having so much despatched the true business of life that the eldest rarely attains to that immense knowledge, and the youngest enter not into the world with more innocency. Whosoever leads such a life needs be the less anxious upon how short a warning it is taken from him."

Happy, indeed, is the man who could have so lived as to deserve such an epitaph, and happier still is he who, like Falkland, had a friend who could write that epitaph in such words as those which were chosen by Clarendon.

JOHN EVELYN AND SAMUEL PEPYS.

It would be hard to leave out of the list of the writers of this time the names of John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys. John Evelyn (b. 1620, d. 1706) was a gentleman of good position, whose famous house at Wotton, in Surrey, still preserves many memorials of his active and busy life. For many years he kept a Diary of the events which took place, and this Diary is one of the best and most interesting accounts of daily life in Stuart times.

Equally interesting, and far more amusing, is that wonderful book "The Diary of Samuel Pepys." The son of a tailor, Samuel Pepys (b. 1632, d. 1703), succeeded by his own industry, mother-wit, and good sense in raising himself to the position of a Minister of State and in becoming Secretary to the Admiralty. His Diary, which was kept from day to day from 1660 to 1669, was not intended to be seen by his friends. He therefore puts into it many things which, no doubt, would otherwise not have found a place there, but this fact makes it all the more interesting and valuable to those who can read it now. Few more delightful and amusing books have ever been written than "Pepys's Diary," and no book gives a better picture of life in London after the Restoration than this Diary of sharp-witted, sharp-tongued, merry Samuel Pepys.

There is only room here to quote one short passage from "Pepys's Diary," but it is worth putting in because it shows us what a pleasant, cheery fellow the good Mr. Pepys was. He is going down the river to see a friend when all the world in London was in terror of the Plague. This is his account of his journey: "By water at night late to Sir G. Cartwright's, but, there being no oars to carry me, I was fain to call a sculler that had a gentleman already in it, and he proved a man of love to music, and he and I sung together the way down with great pleasure. Above 700 died of the Plague this week."

["Pepys's Diary," July 13th, 1665.]

LOVELACE.

A word must be said of some of the other writers in the early Stuart period, because, though they are not such well-known persons as Milton, Dryden, or Bunyan, their works are still known and read by many. Richard Lovelace, the poet of the Cavaliers (b. 1618, d. 1658), had hard treatment from the king he served, for he was sent to prison by King Charles for presenting a petition during the time of the Long Parliament. It was in his prison that he wrote the famous lines to his lady-love, which begin--

"Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage,

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for a hermitage."

HERRICK.

Robert Herrick (b. 1591, d. 1674) was also a Royalist. He was a clergyman, and Cromwell turned him out of his vicarage, to which he only returned after the Restoration. He was the writer of many pretty and graceful verses, of which one of the best known contains the lines:

"Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles to-day

To-morrow will be dying.

"The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun,

The higher he's a-getting,

The sooner will his race be run,

The nearer he's to setting."

WALLER.

Edmund Waller (b. 1605, d. 1687) was a third Royalist writer of pretty poetry which made him famous in his own day, and which has prevented his name from being forgotten in our time.

COWLEY.

Abraham Cowley (b. 1618, d. 1667) was yet another Royalist poet, who received but small reward from Charles II. for the services he had rendered to the Royal cause. Very few of the poems of Cowley have lived to the present day.

THE DRAMATISTS WYCHERLEY AND CONGREVE.

After the Restoration we come to the names of several English writers who were very well known in their day as the writers of plays. Among them the best known were William Wycherley (b. 1640, d. 1715), author of "The Plain Dealer" and many other plays, and William Congreve, a later writer (b. 1670, d. 1729).

The plays written by Wycherley and Congreve are very clever, but there is much that is disagreeable and bad in them. The fact is that under the rule of the Puritans men had been forbidden any form of amusement. When the Restoration came, therefore, there came with it a sudden change -- too sudden, indeed, for the country. Men were not content with reasonable amusements; they thought of nothing but self-indulgence, and they said and wrote many things which had better have been left unsaid or unwritten -- as though, having gone to one extreme in the matter of strictness, they were determined to go to the other in the way of freedom from all restraint and good order.

BURNET.

We must not pass over the Revolution without mention of Gilbert Burnet (b. 1643, d. 1715), whose famous history of the Reformation in England was written in the reign of Charles II., and who was most active in helping to bring about the change of government which led to William III. being placed upon the throne. Besides his history of the Reformation, Burnet wrote other well-known books on religious questions. He was Bishop of Salisbury when he died.

Chapter 62. Writers of the Later Stuart Period.

The Essayists. (ch 62)

"Writers, especially when they act in a body and in one direction, have great influence on the public mind." -- Burke.

So far we have spoken only of the writers whose names were known before the Revolution, but we must not forget that Queen Anne was a Stuart no less than Charles II., and that we must not, in the history of the Stuart Period, fail to mention the famous writers of Queen Anne's time. It is right to mention them apart from those of whom we have spoken in the last chapter, for there is the greatest possible difference between the writers of the last half of the seventeenth century and those of the first half of the eighteenth century. It is in Queen Anne's time that we come to the great Essayists, the writers of short papers or essays. Such were Joseph Addison (b. 1672, d. 1719), Sir Richard Steele (b. 1671, d. 1729), and Jonathan Swift (b. 1667, d. 1745).

ADDISON.

At a time when newspapers were scarcely known, short essays, written by Addison, Steele, and Swift, were very widely read, and had a great influence upon people's minds. In "The Tatler," a sort of magazine which was started by Steele, Addison wrote a number of famous papers in which he attacked his enemies the Tories; but his most famous writings were in "The Spectator," which first began to appear in 1711. It was in the "Spectator" that the famous letters of Sir Roger de Coverley appeared. Sir Roger was supposed to be a kind-hearted, shrewd, country gentleman, who gave his views on a variety of subjects from politics and poetry to gardening, the fashions, and the trimming of wigs. Besides his writings in the "Tatler," "Spectator," and other magazines, Addison wrote a play called "Cato" and a considerable amount of poetry.

SWIFT.

A still greater name than that of Addison is Jonathan Swift, who was born in Dublin in the year 1667. Perhaps Swift is most famous nowadays as the writer of "Gulliver's Travels" a book which can still be read by anyone who is in search of an amusing story; but when Swift wrote the account of Gulliver among the Pigmies of "Lilliput," or among the Giants of "Brobdingnag," he not only meant to write a witty and amusing story, but to make his political enemies smart by the sharp things he said of them, and to ridicule many of the ideas and doings of Englishmen of his day.

The whole story of Gulliver is full of passages which were meant to raise a laugh against Swift's bitter enemies the Whigs, or to win favour for his friends the Tories. In order really to understand "Gulliver's Travels," it is therefore necessary to know something of the history of the time and to understand what are the thoughts Swift had in his mind when he wrote.

Among the other famous writings of Swift are "A Tale of a Tub" and "The Battle of the Books." These are, like "Gulliver's Travels," satirical writings in which the author attacks his enemies by means of humorous stories and witty comparisons. So great was Swift's power of saying sharp and witty things that he came to be looked upon by the Tories as one of their best champions, and to be feared by the Whigs whom he so bitterly attacked.

In 1713 Swift was made Dean of the Cathedral of St. Patrick in Dublin. Irishmen are justly proud of the great and brilliant writer, who was born and lived so long in the city of Dublin. Towards the end of his life Swift lost his reason. He died in 1745 at the age of 78.

STEELE.

There is little room here to speak of Steele (b. 1671, d. 1729). He was one of the famous essay-writers who joined with Addison in writing for "The Spectator" and "The Guardian." He began life in the army, but early gave up the sword for the pen. Towards the end of Queen Anne's reign he entered Parliament, but was turned out of the House for writing what was declared to be treasonable literature. Under George I., however, he was taken back into favour. The names of Addison and Steele always go together as those of writers of clear and beautiful English prose.

DEFOE.

Daniel Defoe (b. 1661, d. 1731) was a busy politician and an active man during his lifetime, but it is not by his politics that he is remembered. It is as the writer of that wonderful story "Robinson Crusoe," which every English boy and girl knows, or ought to know, that Defoe will be remembered as long as the English language is read. "Robinson Crusoe" in his coat of skins and carrying his umbrella, "Man Friday," the Dog, the Goats, the Parrot, are friends of whom we never grow tired, and who seem just as real to us as any of the people who lived and died, and whose stories are told in this book. Besides "Robinson Crusoe" Defoe wrote several other stories, of which "The Life of Captain Singleton" and "The History of Colonel Jacque" are the best known. His "History of the Plague of London" is also a book of the greatest interest.

Pope -- Early Newspapers (ch 62)

"Why did I write? What sin to me unknown

Dipp'd me in ink -- my parents', or my own?

As yet a child, nor yet a fool to fame,

I lisp'd in numbers, for the numbers came."

Pope (writing of himself in "Prologue to Satires")

POPE.

Perhaps the greatest name among the writers of the later Stuarts is that of Alexander Pope (b. in London 1688, d. 1744). He began writing when he was quite a child, and throughout the whole of his life was seldom idle. He wrote little that was not worthy of a great writer. In 1715 he published the first part of his translations of the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey" of Homer, the wonderful Greek poems which describe the Siege of Troy, and the Ten Years' War between Greeks and Trojans, and the wanderings of Ulysses. Here are some lines taken from Pope's translation, which show the form of his poetry.

The lines describe how the great Trojan hero, "Hector," bids farewell to his wife and child, before going to battle:

"Thus having spoke, th' illustrious chief of Troy

Stretch'd his fond arms to clasp the lovely boy;

The babe clung crying to his nurse's breast,

Scared at the dazzling helm and nodding crest.

With secret pleasure each fond parent smiled,

And Hector hastened to relieve his child:

The glittering terrors from his brow unbound,

And placed the gleaming helmet on the ground;

Then kiss'd the child, and lifting high in air,

Thus to the gods preferr'd a father's prayer--

'O Thou! whose glory fills th' ethereal throne,

And all ye deathless powers! protect my son!

Grant him, like me, to purchase just renown,

To guard the Trojans, to defend the crown,

Against his country's foes the war to wage,

And rise the Hector of the future age!'" --Bk. VI.

It cannot be said that Pope's translation of this great poem is the best and most correct that has ever been made, but the writing is so fine and spirited that we can admire it for itself, even when it does not give quite a true idea of the words and thoughts of the writer of the "Iliad." The "Essay on Man" is a most wonderful piece of writing. Every line of it seems to be fitted and polished with the same marvellous care. There are very many that have not read the "Essay on Man" who, nevertheless, are familiar with many of the lines which it contains. There is hardly any poem in the English language from which lines are more often quoted by writers, by speakers, and in ordinary conversation. It is in the "Essay on Man" that we find, among many other equally well-known passages, the lines which describe the nature of man:

"Know, then, thyself, presume not God to scan;

The proper study of mankind is man.

Placed on this isthmus of a middle state,

A being darkly wise, and rudely great:

With too much knowledge for the sceptic side,

With too much weakness for the stoic's pride,

He hangs between; in doubt to act, or rest;

In doubt to deem himself a god, or beast;

In doubt his mind or body to prefer;

Born but to die, and reasoning but to err;

Alike in ignorance, his reason such,

Whether he thinks too little or too much;

Chaos of thought and passion, all confused;

Still by himself abused, or disabused;

Created half to rise, and half to fall;

Great lord of all things, yet a prey to all;

Sole judge of truth, in endless error hurled;

The glory, jest, and riddle of the world!"

Very familiar, too, are the following lines:

"Hope humbly, then; with trembling pinions soar;

Wait the great teacher Death; and God adore.

What future bliss, He gives not thee to know,

But gives that hope to be thy blessing now.

Hope springs eternal in the human breast:

Man never is, but always to be blest."

The "Dunciad," a satire, and the "Rape of the Lock" are among other well-known poems by Pope.

NEWSPAPERS.

We must not leave the subject of writers and literature without mentioning the beginning of one great branch of writing which has become very important in our own day. Before the Stuart time small printed sheets giving news had from time to time been issued on special occasions; but it was not till the days of Charles I. that we find anything like a real newspaper such as we are acquainted with at the present day.

It was during the Long Parliament that the practice began of printing a regular account of what took place in the two Houses, and this account was called "A Diurnal" -- or, as we should say, "Journal," or "daily." On the following page is a picture of a page from one of these diurnals, greatly reduced in size. The date on it is the 15th of January, 1643. "The Diurnal" was soon followed by many other newspapers, till in our day there is scarcely a town in the kingdom that has not got its daily or weekly newspaper.

Chapter 63. Science, Art, and Daily Life Under the Stuarts.

The Royal Society -- Newton and Wren -- Harvey. (ch 63)

"See worlds on worlds compose one universe,

Observe how system into system runs,

What other planets circle other suns."

Pope: "Essay on Man."

We have spoken of the band of famous writers who lived in the Stuart period, and we have divided them into two sets -- those who lived and wrote in the earlier period, before the Revolution, and those who lived and wrote during the last years of the period, and chiefly in the reign of Queen Anne. We have now to speak of two great Englishmen, who were among the most famous of all the men of their time, and whose work was done in the Stuart period -- the one a great mathematician, the other a great architect.